Why Being "Correct" Isn't Enough

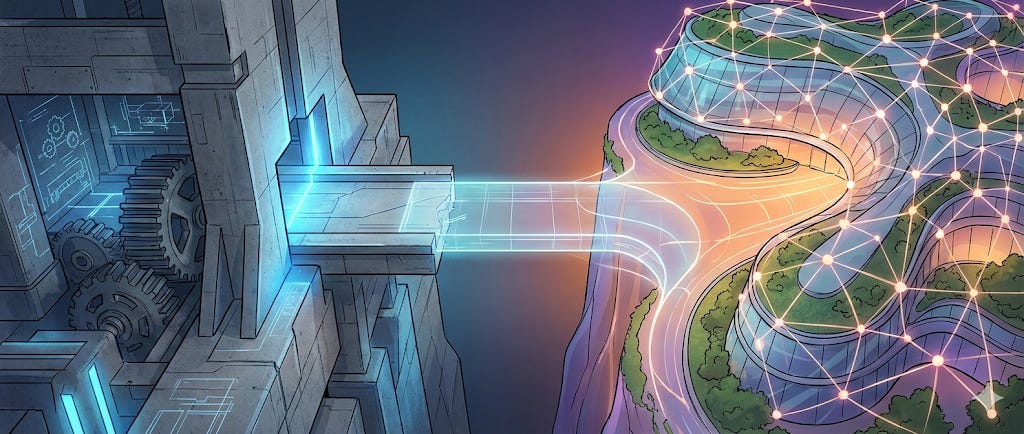

Bridging the Gap Between Slavic Engineering Culture and Big Tech Leadership

I’d love to talk about a specific friction point in the tech industry that rarely gets discussed openly. It is the clash between the communication style common in engineers raised in Slavic cultures and the “soft skill” expectations of Western Big Tech companies.

I have seen this pattern repeat itself many times: A technically brilliant engineer - someone who can architect complex systems in their sleep - walks into a Senior or Staff-level interview. They have the knowledge. They have the experience. But they fail the behavioral or system design interview.

Why? Because they were trying to be right, while the interviewer was looking for them to be collaborative.

The Cultural Default: Debate as Validation

There is a distinct communication style prevalent in Slavic cultures (and often Central/Eastern European cultures in general). It is characterized by a healthy dose of cynicism and a dialectic approach to problem-solving.

In this context, the goal of a conversation is often to strip away the fluff and get to the absolute “truth.” If I disagree with you, I will forcefully argue my point - not because I don’t respect you, but because I respect the technical problem enough to ensure we don’t implement a suboptimal solution.

In this framework, “winning” the argument means the best idea prevailed. It is a meritocracy of ideas, fought with verbal combat.

The Big Tech Expectation: The Art of the Trade-off

However, the culture in large US-based tech companies (the FAANGs of the world) operates on a different frequency, especially as you climb the ladder.

When you are a junior or mid-level engineer, your job is often to find the “right” answer. But as you interview for Senior, Staff, or Principal roles, the game changes. There are rarely “right” answers anymore. There are only compromises.

At this level, leadership isn’t about proving you are the smartest person in the room. It is about:

Identifying multiple viable solutions.

Weighing the pros and cons of each (latency vs. consistency, cost vs. speed).

Building consensus around a solution that everyone can live with.

The Interview Trap

This is where the cultural disconnect becomes fatal during interviews.

Imagine a system design scenario where the interviewer proposes a constraint. The Slavic engineering instinct might be to immediately spot why that constraint is “wrong” or “stupid” and forcefully argue against it to steer the ship toward the “correct” technical path.

To the candidate, this feels like leadership. They are saving the company from a bad decision!

To the interviewer, however, this looks like rigidity. They don’t see a “guardian of quality”; they see someone who:

Does not listen to requirements.

Cannot accept alternative viewpoints.

Will be difficult to work with in a cross-functional team.

The forceful argument - the very instinct that helped this engineer succeed technically in earlier roles - is now the red flag preventing their promotion.

The Shift: From “I am Right” to “Here are the Options”

For engineers from this background looking to break into senior leadership in the US market, the challenge isn’t learning more tech. It is unlearning the need to win the argument.

The goal must shift from “Proving X is the best way” to “Demonstrating that I understand the cost of choosing X over Y.”

It is a subtle shift, but it changes the entire dynamic of an interview. It moves you from an adversary to a partner.

Actionable Advice: The Dictionary of Diplomacy

If you recognize yourself in this description, the solution isn’t to change your personality. You don’t need to become fake or overly enthusiastic. You just need to change your framing.

Here are three specific shifts to make during your next interview:

1. Replace “No” with “Yes, and...”

In a design interview, when an interviewer suggests a requirement that sounds technically weak, the instinct is to say: “No, that won’t work because the latency will be too high.”

This shuts down collaboration. Instead, try the “conditional yes”:

“We can definitely design it that way. If we do, we should be prepared for higher latency. Is that a trade-off we are willing to make for this specific feature?”

You are still pointing out the technical flaw, but you are framing it as a business decision rather than a personal error.

2. Move from Absolute to Relative

Slavic languages and culture often favor directness. In English tech culture, directness can sound like arrogance.

Don’t Say: “The best database for this is PostgreSQL.”

Do Say: “PostgreSQL is a strong candidate here because of its ACID compliance. However, if we expect massive write volume, we might hit a bottleneck, so we should consider DynamoDB as an alternative.”

Senior engineering is rarely about the “best” tool; it’s about the “least bad” tool for the specific constraints. Showing you see the bottleneck makes you look senior; claiming one tool is “the best” makes you look junior.

3. The “Steel Man” Technique

Before you tear an idea down, build it up. If the interviewer (or a potential conflict partner) proposes a solution you hate, force yourself to state one benefit of their idea before you critique it.

“I see why you suggested X - it would definitely simplify our deployment pipeline. My concern is that it introduces a single point of failure in the load balancer. How would we mitigate that?”

This signals that you are listening to understand, not just listening to reply.

The Bottom Line

Reaching the Staff or Principal level requires a fundamental shift in how you view your value.

Junior Value: I write code that works.

Senior Value: I stop bad code from being written.

Staff/Principal Value: I create an environment where the team can agree on what to build, even if it’s not exactly what I would have built alone.

Your technical cynicism is a superpower for finding bugs. Don’t let it become a bug in your career growth.

This is such a gem and it hits home 100%. It is uncomfortably accurate in the best way. It felt like someone politely but very clearly called me out.

Valuable insights from an experienced manager. I strongly recommend that younger colleagues, especially those from Eastern Europe, take the time to read, understand, and put them into practice. Thank you for sharing, Vladimir—please keep up the excellent work.