How to Disagree with your Manager Without Getting Fired (or: The Art of the "Soft No")

Why your "honest feedback" sounds like "insubordination"—and the one technique that fixes it.

Imagine this scenario:

You are in a planning meeting with your Director. They get excited about a new feature and ask, “Can we squeeze this into the Q3 release? It’s critical for the marketing launch.”

You know the codebase. You know the team is already burning out. You know that adding this feature will destabilize the entire platform.

If you are an engineer from a culture that values directness (Slavic, Germanic, Dutch), or just a senior engineer who cares about uptime, your first instinct is to protect the system. You look them in the eye and say:

“No. That is impossible. We are already at capacity, and that feature requires a backend refactor. We can’t do it.”

You think you just saved the company from a disaster. The Director thinks you are a “blocker.” A “naysayer.” Someone who “doesn’t have a can-do attitude.”

Why? Because in American corporate culture, “No” is a trigger word. It signals a dead end.

The Disconnect: “Guardian of Truth” vs. “Partner in Crime”

In many engineering cultures, professional respect is shown through technical honesty. If I see a hole in the bridge, I scream “Stop!” I am not attacking the driver; I am saving the car. To lie about the hole would be a betrayal.

But in Big Tech leadership, the game is different. Executives do not want to be told what they can’t do. They want to be given choices.

When you say “No,” you are taking away their agency. You are making the decision for them.

When you say “Yes, and...”, you are giving them the agency back, but forcing them to pay the price.

The Solution: The “Yes, And...” Technique

This is a concept borrowed from Improv Comedy, but it is one of the most powerful tools in a Senior Engineer’s kit.

The rule is simple: Never negate the reality. Build on it to show the cost.

Instead of acting like a Wall (blocking the request), act like a Mirror (reflecting the consequences).

Here are three examples of how to transform a career-limiting “No” into a strategic “Yes.”

Scenario 1: The Impossible Timeline

The Request: “We need this launched in 2 weeks.”

The Gut Instinct: “That is ridiculous. We need 6 weeks minimum. It can’t be done.”

The “Yes, And” Pivot:

“We can definitely aim for a 2-week launch. However, to hit that aggressive date, we would need to skip the integration testing phase and cut the reporting feature. Are you comfortable releasing with that level of risk, or should we stick to the 6-week plan to ensure stability?”

Why this works: You didn’t say no. You said yes, but you attached a terrifying price tag (no testing). Now, the manager has to say, “Okay, let’s wait 6 weeks.” You got what you wanted, but they made the decision.

Scenario 2: The “Shiny Object” Syndrome

The Request: “We should use [Trendy New Database] for this, I read it’s faster.”

The Gut Instinct: “No, that database is unstable and we don’t have anyone who knows how to maintain it. It’s a bad idea.”

The “Yes, And” Pivot:

“That’s an interesting technology, and it definitely has speed advantages. If we choose to go that route, we will need to pause our current roadmap for a month to train the team and hire a specialist to support it. Do you think the speed gain is worth that delay?”

Why this works: You validated their idea (”interesting technology”) but framed the “No” as a resource allocation problem. You aren’t being negative; you are being a responsible budget manager.

Scenario 3: The Feature Creep

The Request: “Can we just add this one small button? It’s easy.”

The Gut Instinct: “It’s never ‘just one button’. That touches the API, the database, and the UI. No.”

The “Yes, And” Pivot:

“We can absolutely add that button. To make space for it in this sprint, we will need to remove the ‘User Profile’ update we planned. Which of those two features brings more value to the customer right now?”

Why this works: This is the Conservation of Mass. You are showing them that engineering capacity is a fixed pie. You are happy to slice it differently, but you can’t make the pie bigger.

The “Contractor” Mindset

Think of yourself less as a Gatekeeper (who says who gets in) and more as a General Contractor.

If you hire a contractor to build a house and you say, “I want to add a third floor,” a good contractor doesn’t say “No, that’s stupid.”

They say, “Sure! That will be an extra $50,000 and two more months. Sign here.”

By shifting from Moral Opposition (”This is a bad idea”) to Transactional Cost (”This idea costs expensive resources”), you remove the emotion. You stop being the “Grumpy Engineer” and start being the “Strategic Partner.”

The next time you feel that “No!” rising in your throat, swallow it. Take a breath. And say:

“Yes, we can do that. Here is the bill...”

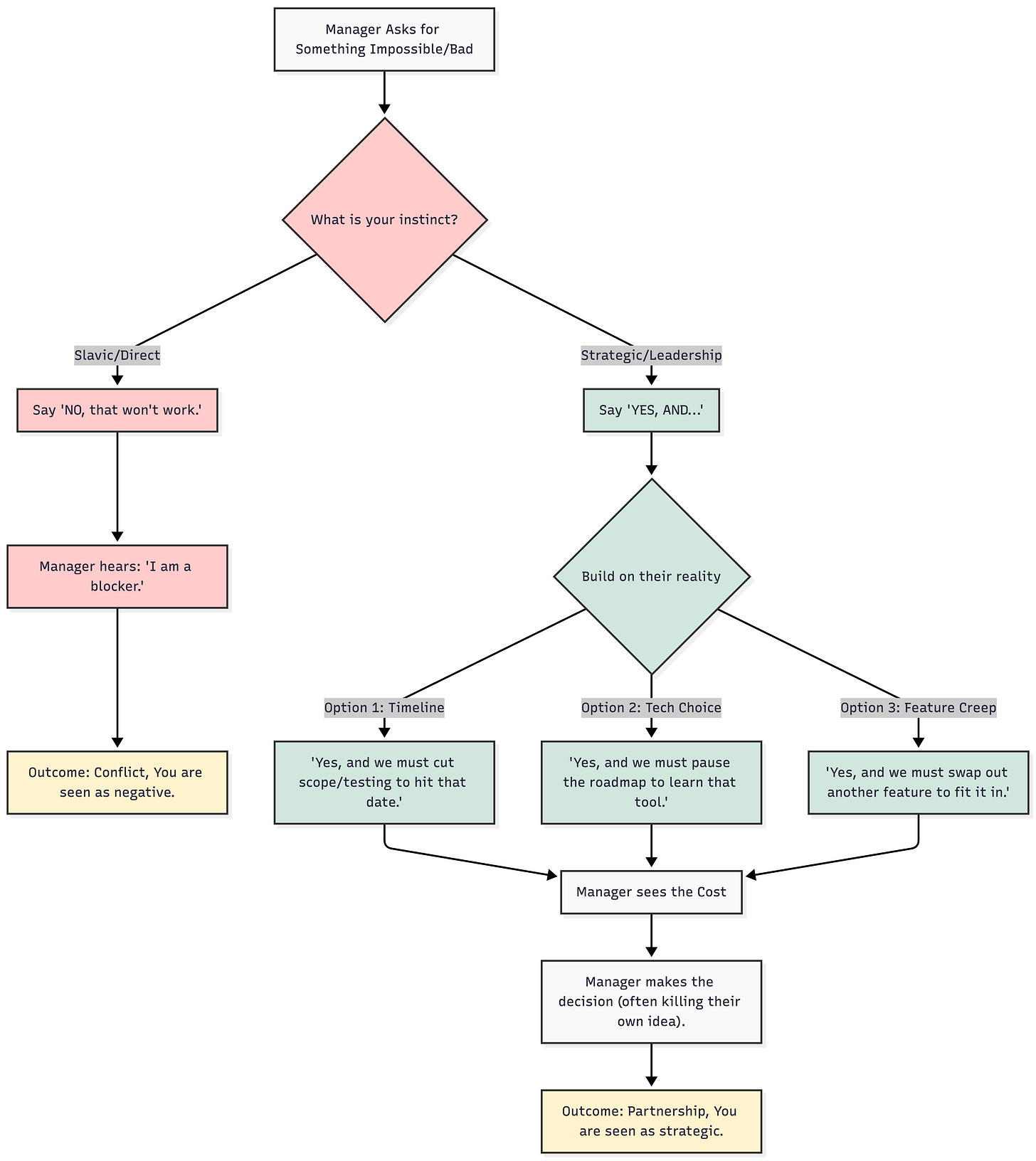

Flowchart

Because who doesn’t love a colorful flowchart.

Learn More

Here is some more stuff you can explore:

1. The Theory: The Power of a Positive No by William Ury. Ury is a Harvard negotiator. He frames the “Positive No” not as being nice, but as protecting your core interests. His formula (Yes-No-Yes) is the academic version of the “Bill of Materials” method I described above.

2. The Mechanism: “Yes, And” in Engineering This isn’t just for comedians. “Yes, And” is the basis of collaborative problem solving. When you stop blocking (saying “No”) and start building (saying “Yes, and it costs X”), you move from being an obstacle to being a constraint. And engineers love constraints. Do note the subtle addition to the concept.

3. The Video: How to Disagree with Your Boss and Not Lose Your Job A solid breakdown of the difference between “defiance” (I won’t do it) and “dissent” (I think this is a mistake). Dissent is loyal; defiance is not. The “Bill of Materials” mindset keeps you firmly in the “loyal dissent” category.